Walter Rowley Thomas, the first born son of Walter Samuel and Alice Thomas was, as tradition dictated, named after his father, however presumably to avoid family confusion he was sometimes referred to as “Rowley,” but commonly referred to himself as “Walt.”

He was kind natured and popular with friends and neighbours in Glendare Street. He completed his education at the Technical School, Boot Lane, Bedminster.

|

| Technical School, Boot Lane, Bedminster. |

His journey to school necessitated walking well over a mile in each

direction, his route took him along the Feeder Road, under the railway bridge

at Temple Meads and across onto Clarence Road, at least a 40 minute walk.

On leaving school he followed his father and began work at the local

Soap works and then to Lysaghts where he worked as a Spelterman. Spelter was a

zinc based metal often mixed with lead and used as a cheaper alternative to

bronze.

The working day was a long one and the labour was hard, however Walt

was still able to indulge in his passion; playing the cornet. He was a gifted musician

and often entertained family and friends with his playing.

He was a good looking and athletic young man, charming and a big hit

with the girls. He flirted with other local teenagers particularly the Willmott

girls, Florence and Lillian who lived a few doors away in 50 Glendare Street.

His younger sister Alice was especially fond of him; she wasn’t able to

relax in bed without first making sure he was asleep in the room opposite.

With the two bedroom doors left open she would shout “Walt, I can’t

hear you breathing?”

If she got no reply she knew he was asleep and consequently felt

secure.

His younger brother Wallace, known by his family nickname “Broncho,”

often suffered with ailments and illness; he was also comforted knowing his

older, stronger and fitter brother was asleep nearby.

On 4th August 1914 Britain declared war on Germany to protect the

neutrality of Belgium, which had been invaded by the Germans on their way to

fight the French.

Lysaghts normally received their supply of zinc from the Belgian city

of Liege, but the German invasion had interrupted supplies. On the morning of

the 7th August a mass meeting of a 1000 men was held at the Netham Works. The

management reluctantly informed the staff they were to be placed on short time

working with an unfortunate reduction in wage. Instead of the expected anger

the men broke into cheers shouting hurrah for King George V and the Allies.

Overcome with patriotism and war hysteria many pledged to join “Kitchener’s”

new army, including Walt.

Nine days after the meeting, the local Western Daily Press newspaper

published an open letter signed by the Lord Mayor; Sheriff of Bristol, and a

host of other local dignitaries. The letter carried the headline, “Lord

Kitchiner’s call to arms,” “Appeal to the citizens of Bristol.”

The letter made reference to, “a tremendous struggle; the strain will

be long, and everything may turn upon the strength we can throw into the field

when the most critical stage arrives.”

It went onto explain General Kitchiner’s plan to bolster the British

Army with an additional 100,000, “able-bodied patriotic young men between 19

and 30.”

Rowley wasn’t quite old enough; but undeterred and no doubt accompanied

by friends, he visited the central army recruiting office within the Colston

Hall, in the City centre. The Western Daily Press described conditions inside

for those wanting to sign up.

“Around the walls are arranged six or eight tables and screens and near

each are a weighing machine, an appliance for registering the height of a would

be soldier, and the printed cards usually seen in the opticians window for

testing eyesight.” The men were then sent upstairs where their personal details

were recorded before being thoroughly but quickly medically examined by a

doctor to ensure they were “physically sound.”

The result of the examination along with vaccinations, religion,

occupation and all the man’s measurements and other details were all carefully documented.

An average of 300 young Bristolians were being recruited every day.

Walter may have lied about his age, or the recruiting team may have

turned a blind eye, either way, he signed his attestation papers and enlisted

into the Somerset Light Infantry.

The Western Daily Press also

reported the scenes outside the Colston Hall at the time he enlisted, “crowds

thronged around the Colston Hall Recruiting Station and soon after eleven o’clock

there was a great march out of new recruits for the Somerset Light Infantry.”

Returning home, Alice was in the kitchen with 10 year old Alice, the

other children were playing outside. Walter had been unusually absent for a few

hours and was uncharacteristically quiet and subdued. Sensing something wrong

his mother said, “Walt, what’s the matter, why are you so quiet?”

“I’ve joined the army,” he replied.

“Why?” she asked.

“It was the Willmott girls, they was teasing me saying why aren’t you

joining up to fight?”

Maybe it was fear of being perceived as a coward or, just as likely,

patriotic fervour; whatever the reason, like many Lysaghts employees, Walter

Rowley Thomas was now Private 10538 Thomas of the 6th Battalion, Somerset Light

Infantry a brand new infantry battalion. Within days he said good bye to the

family and made his way to Jellalabad Barracks in Taunton via train journey

from Temple Meads. After a short stay the men moved again this time to the Tourney

Barracks in Aldershot. Soon after arriving he wrote a letter home.

Pte W.R.Thomas

10,538 D. Company

G. Block,

Tourney Barracks,

Aldershot

Dear Mother and Father,

It was good of you to send me those things and I enjoyed those bananas & I am feeling better. I am glad that Gilbert has got home but I am sorry for Uncle Peter. Gilbert wouldn’t be able to come in our Battalion because we are full up. About that allowed money it is only for widowed Mothers and Fathers. Dear Mother I am keeping my money to buy some presents Christmas & it wont be long now, so I hope you wont mind. We have been doing a lot of skirmishing & lying about in the wet grass I have caught this cold. I have taken some pills, and I feel a little better. They sent our advance guard to Witley last Friday but they called them back. We are likely to go any day, so I shouldnt write until I know the truth. The first lot of Kitchener’s army went to France last Saturday. They were Scotch Highlanders, but I don’t know the name of their regiments. I hope you are all well. I will bring Father a present from your ever loving son.

It was good of you to send me those things and I enjoyed those bananas & I am feeling better. I am glad that Gilbert has got home but I am sorry for Uncle Peter. Gilbert wouldn’t be able to come in our Battalion because we are full up. About that allowed money it is only for widowed Mothers and Fathers. Dear Mother I am keeping my money to buy some presents Christmas & it wont be long now, so I hope you wont mind. We have been doing a lot of skirmishing & lying about in the wet grass I have caught this cold. I have taken some pills, and I feel a little better. They sent our advance guard to Witley last Friday but they called them back. We are likely to go any day, so I shouldnt write until I know the truth. The first lot of Kitchener’s army went to France last Saturday. They were Scotch Highlanders, but I don’t know the name of their regiments. I hope you are all well. I will bring Father a present from your ever loving son.

Walt

xxxxxx

xxxxx

His first three months were spent training at the Aldershot military

camp. At some point while still in England, he joined the Battalion band. The

musicians assembled for an official photograph, Walter can be seen in the

fourth row from the front, second from right.

Life at the barracks wasn’t all hard work; there were lighter moments

when the men could enjoy themselves. The Commanding Officer Colonel Rawlings

arrived in camp in early November. His arrival provided an excuse for the

Battalion to stage a musical extravaganza in his honour, the band played and

several soldiers sang, or gave solo recitals; the celebrations concluded with

everyone singing La Marseillaise and the national anthem.

Around Christmas time the Battalion moved to Witley camp in Goldalming,

Surrey before returning to Aldershot in March 1915 where they stayed until

orders came to leave for France.

|

| Walter 4th row from the front, 2nd from right. |

Late in the afternoon of Friday 21st May 1915, the men boarded a train

to Folkstone and by 6.30 pm were on their way to France aboard the South

Eastern and Chatham Railway ship Invicta. It was an uneventful crossing

arriving in Boulogne 4 hours later.

Having disembarked they marched to the Ostrohove rest camp overlooking

the town and near to the railway station, eventually getting to bed by 1.30am.

It had been a long day.

After two days rest they received orders to transfer to an unknown

destination.

It was a hot day with light winds and Walt, like the other soldiers,

had to carry his blankets and waterproof sheets in addition to the usual

military equipment. After an hour and a half they arrived at St Bricque railway

station and boarded a train to Cassel.

On arrival in Cassel the men prepared for a Three hour march to the

village of Buysseheure. It was an exhausting 8 mile journey, the excessive

weight of their packs made marching extremely difficult. The Battalion stopped

every 45 minutes for a 10 minute rest but despite this and their general good

health, fitness, and spirits, 20 men collapsed through exhaustion. Thankfully

on reaching their destination in the early evening, a cool breeze replaced the

heat of the day.

After almost a week the Battalion received more orders to move out, a

much shorter march to the small village of Noordpeene.

This time Walt and the other men carried much lighter packs and were no

longer required to carry their thick, heavy greatcoats described at the time as,

“this most heavy cumbersome and useless garment.”

In place of the greatcoat each man carried a waterproof sheet, blanket

and a cardigan jacket.

The next day, 28th May 1915, they marched to Eecke via Cassel and

Baileul.

The following day the men were inspected by General Fergusson and two

days later were on the road again, this time marching across the Belgium border

to the small town of Scherpenberg.

It had been another difficult trek hampered by high winds and traffic

around the Baileul area. They stayed in Scherpenberg for over a week digging

support trenches to secondary positions west of Ypres, and later, digging

through the night, support trenches on the east side of Mount Kemmel.

The German trenches were visible, only 1500 – 1700 yards away.

Consequently during the day there was sporadic gunfire.

At night only occasional gunfire disturbed the darkness and the

digging. Occasionally German searchlights scanned the area and snipers were a

constant threat. One night a couple of houses were accidentally set on fire in

the hamlet of Dickebusch and, on 4th June, a soldier was hit by night time

gunfire while standing on the parapet of a trench.

Walt’s first experience of front line trench warfare came soon after.

On 12th June the Battalion received orders to leave Scherpenberg. They

were gone by 7.15 am reaching their new billets on the Baileul – Neuve Eglisse

Road by 10am.

Two companies joined the 5th Battalion of the North Staffordshire

regiment in the front line trenches, while the remaining two companies stayed

in their billets. Three days later the remaining two companies replaced the

others at the front.

It’s not possible to be sure if Walt was involved in the first or

second deployment, but by 19th June the whole Battalion had taken part and felt

the war up close, coming under both artillery and infantry fire.

The more experienced North Staffordshire regiment were acting as

instructors and had not previously encountered “Kitcheners.” Whatever their

expectations had been they were impressed and full of praise for the “bearing

and behaviour” of this new group of volunteer soldiers.

On 20th June the Battalion were on the move again setting out at 9.45pm

and marching through the night to join up with the rest of 43 Brigade.

They arrived in Poperinge via Locre at 2.35pm and were billeted about 1

½ miles from the village centre. The 43rd Brigade was billeted in depth along

the Poperinge to Watou road.

Two days later the brigade received orders to move up and relieve 43

Brigade in trenches east of Ypres.

After 4 hours marching, the Battalion stopped for tea at Vlamertinge

arriving in Ypres at 9.15pm.

Ypres, a small, historic city in the very western part of Belgium, was

in a terrible state, streets of shattered houses and the famous Cloth Hall, not

ruined but badly damaged, it was a general scene of desolation.

While the Battalion waited and waited, they endured intermittent

shelling reporting one casualty from artillery, and another from rifle fire. Finally

the relief was complete and the men settled in to the trenches by 2.30am.

The trenches were in a dangerous position having been captured from the

Germans only a few days previously. They occupied the most easterly point of

the British position in Belgium, in front of Hooge, a small village on the

Bellewaerde Ridge, about 4 kilometres east of Ypres.

Walt and his colleagues came under heavy bombardment. The 6th Battalion

war diary records:

“Trenches have been under continuous but light artillery fire until 9.45pm when a violent bombardment for a few minutes caused some damage. The parapets of C5 and C1 were repeatedly hit and high explosives and shrapnel were continually used against the new communication trenches in rear of C4 and C2. Also against C11 and into the field behind causing little damage. Two rapid bursts of 8 or 10 guns at the commencement caused some considerable damage to C5, C6 and C12. A shell burst through the Headquarters dugout resulting in Captain A.R.S Lakehill being wounded. A similar case occurred in another trench 3 men being wounded. At dusk 3 men in C5 were wounded, making a total of casualties during the 24 hours of 5 all ranks. An enemy Taube [German monoplane aircraft] was sighted in the evening, and one in the morning of 27th apparently directing the enemy’s fire. The Battalion worked very hard in improvement of the trenches. The behaviour of all ranks was excellent.”

The night was a quiet one; it was thought spies at the rear of their

position were sending information back to the Germans because communications

wires were continually being cut when there was no infantry or artillery fire. Although

the enemy were constantly sapping, [digging trenches “saps” into no man’s land,

sometimes used as listening posts], and wiring, [cutting British barbed wire or

improving their own defensive barbed wire], the Germans appeared to have no

inclination to attack.

The next day the Battalion war diary records:

“Heavy shell fire from 11am to 2pm. High explosives poured upon us. All working parties compelled to cease work.Telegraphic communication destroyed, but re-established by 5pm. Heavy shelling by the enemy was resumed at 7.30pm and continued until 12 midnight.”

Finally, in the early evening of 29th June, Walt and the

rest of the Battalion were relieved by the 8th Rifle Brigade and 7th Kings

Royal Rifles.

The total number of 6th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry casualties

over the five days was 6 officers wounded, 6 other ranks killed, and 43

injured. The Battalion marched back to their billets near to Vlamertinghe where

they stayed for the next two weeks. During that time men were supplied for

working parties, both day and night, but casualties were mercifully light, only

two injured as a result of gunshot wounds.

Although the general health of the Battalion was described as very

good, fresh water was becoming more and more scarce. On 18th July new orders

were received. They were to relieve trenches currently held by the Shropshire

Light Infantry. By 9pm that evening the Battalion had marched through Ypres and

reached the Menin Gate. There they were met by guides from the Shropshire

regiment who escorted them to the front line. It was a difficult handover

taking nearly 2 hours of hard walking to reach the trenches.

This deployment was a challenging one, four men killed and 29 wounded

in that first evening. The war diary records:

“Between 2am and 3am whizzbangs more numerous. At 7.37am a Taube was hit”

Heavy shelling continued on and off for the next few days.

“The enemy opposite our trenches are dressed in dark blue uniforms. One of the enemy worked at some digging in full view of our trenches, and created some interest among our soldiers until he was shot by one of our officers. Our snipers accounted for 3 others.”

“The enemy opposite our trenches are dressed in dark blue uniforms. One of the enemy worked at some digging in full view of our trenches, and created some interest among our soldiers until he was shot by one of our officers. Our snipers accounted for 3 others.”

At just after midnight on 23rd the Battalion were delighted to be

relieved by men from the 10th Durham Light Infantry; however, that night it was

raining heavily, the trenches were subsequently ankle deep in water making the

relief a very difficult process.

Eventually Walt and his comrades withdrew to the ramparts of Ypres, the

ancient fortifications surrounding the city; where they were held in reserve.

For the next three days the Battalion committed 600 – 700 men to large

working parties supplying the frontline soldiers with ammunition and RE stores

such as wire etc.

On 26th July, under cover of darkness the Battalion moved out of the

Ypres ramparts and relocated in a hop field about half way between Vlamertinghe

and Poperinghe, and set about making themselves comfortable in bivouacs.

They were anticipating at least a week’s rest but, only four days

later, a telegram was received at 4.30am, “stand to arms; Germans attacking

41st Brigade.”

“Stand to arms” was an order designed to prepare soldiers for fighting;

each man would be expected to stand on the trench fire step, rifle loaded,

bayonet fixed.

In the coming hours there was some confusion and counter orders, but

around 9pm, C and Walt’s D, company, were ordered to relieve A and B company

who held positions in the firing line at Zouve Wood.

As the men moved off they were held up at the Lille Gate by heavy,

violent enemy artillery fire and had to take cover near the Gate.

Lieutenant A. H. Foley described the scene:

"We moved off, but before we had got clear of the town the bombardment recommenced with such violence that it was impossible to go any further. We waited crouching along under a garden wall opposite the ruins of a church, while around us raged a perfect tornado. Branches of trees were strewn about and pieces of brick and masonry hurtled into the roadway, but luckily our hiding place was not directly subjected to shelling, so we escaped serious damage".

The shelling died down around 10.30pm allowing Walt and the rest of the

men to move towards the GHQ line, finally arriving about 12.50am.

The GHQ line was a well sited defensive line constructed originally by

the French Army, running from Zillebeke Lake (2 1/2 km behind the Allied front

line), to almost a kilometre east of Wieljte, (5 km behind the Allied front

line). At Wieltje it continued in a north-westerly direction to take in

Boesinghe village and its railway bridge. It provided a good field of fire and was

constructed out of a series of well-built redoubts, (defensive fortifications),

at a distance of 350-450 metres apart. The redoubts were joined together by a

thick band of barbed wire entanglements some 5 metres wide with openings only

for roads and tracks. A garrison of about 50 men would hold the position of

each redoubt.

All day long on 1st August, C and D companies were standing to arms,

but at night, on receipt of orders they moved off to reinforce A and B

companies in Zouave Wood.

By midnight A, B, and C companies occupied the firing line in the Wood

with D company in reserve in dugouts known as halfway house.

Overnight, 3rd – 4th August, Walt and the rest of D Company were

ordered to relieve A company in the front line.

A member of D Company, Corporal Loxton, kept a diary and described what

D company found when they reached the trench that night:

“Moved up to the firing line tonight to relieve A company; Worst part of front in the hollow of “U” facing trench captured by Germans, the space between it and us being open ground covered with long grass, and our position being on edge of Sanctuary Wood, beautifully marked off by German artillery. The whole hollow of the “U” was covered with bodies of K.R.R. and R.B’s, killed in original retreat and subsequent counter attacks on retreat, and the stench was awful and the outlook appalling. The captured trench was on rising ground and also beautifully ranged by our artillery, who were dropping in shells all day. It is doubtful whether the Germans occupy the trench at all. If they do, or did, then their losses must have been frightful, as our fire from 9.2 and other guns was terrible, practically every shell dropping in trench or parapet. We saw several bodies on parapet in German uniform, a sign that their losses had been heavy, otherwise they would have been recovered and buried.”

At day break veritable tornados of shells again swept Zouave Wood,

consequently work on the British trenches, repairing blown in parapets etc, was

difficult. When night fell a Somerset soldier had been killed and 37 wounded.

Eventually the 6th Somerset’s marched back to dugouts west of Ypres, however

during the relief the Battalion transport was shelled on the Ypres road causing

10 more casualties. The Germans continued to shell the dugouts so the Battalion

moved out further, to a camp west of Vlamertinghe.

After three days of rest the Battalion were back in action. Orders were

received to relieve the Shropshire Light Infantry at Railway Wood. The trenches

were in a poor state due to constant German shelling raining down on the

British position.

Now in position, the Somerset’s, saw five German airplanes flying over

the area and casualties were beginning to mount, five of the Battalion killed

and 12 wounded.

|

| Ypres from Railway Wood 2016 |

In the coming days the men came under increasingly heavy German

artillery fire from their position at Hill 60. At one point The French

artillery fired gas shells at the Germans occupying an area near Bellwarde

Farm. Some days later there was an

unfortunate incident whereby 5 men were killed and 15 wounded as a result of

friendly fire when an allied artillery shell landed in a trench occupied by the

Somerset’s.

Just after midnight on 17th August the Battalion was relieved and

ordered to return to the ramparts of Ypres and later to the general defence of

Ypres. German artillery was causing lots of damage and casualties. It was a

difficult and dangerous time and no doubt tested Walt and the other men to the

limits of endurance. Sadly, on 19th August, at 4.20am one member of the

Battalion, Private L Phillips was shot for desertion.

The following day orders were received to withdraw overnight to a rest

camp near Watou west of Poperinghe.

September 1915 brought heavy rain to the Ypres area. The Battalion

moved off in company order, to take over all trench stores such as shovels,

picks, corrugated iron, duckboards, etc and where possible, relieve the 6th

Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry.

Walt’s D company were at the front, as they reached the Asylum, outside

the west entrance to Ypres, the Germans fired a number of whiz bangs (small-calibre

high-velocity shells) at them slightly injuring 16 men.

On arrival at the Menin Gate they waited for guides from the Duke of

Cornwall’s and didn’t complete the relief until 1.30am, nine hours after

leaving the rest camp. The week was spent repairing and making good trenches,

and watching artillery shells fired by both sides.

By the 7th September the rain had stopped and the weather was warmer

and brighter. Overnight the Battalion was relieved by the Buckinghamshire light

infantry; unfortunately three men were killed and 33 wounded during the relief.

A week later they returned to the GHQ line south of the Ypres – Menin

road. It was a comparatively peaceful period with few casualties and lighter

artillery.

The Battalion war diary records:

“enemy aeroplanes active in evening and early morning.”

On the 24th September they boarded a train for Ypres. Orders had been received there was to be a second attack on Bellewaarde.

They reached the Asylum in the early evening and detrained. The roads were wet from recent rain but it was a quiet, clear night with the moon obscured by clouds and only intermittent rifle fire.

By 11pm B, C and D companies were settled into the GHQ line. In the

still of the night the men waited then, at 3.50am, the guns opened up an

intense bombardment of the German lines extending from Railway Wood to

Sanctuary Wood. At precisely 4.19am a mine beneath the German positions was

detonated. A minute later the British, consisting of the Shropshire Light

Infantry, Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, and the 9th Rifle Brigade,

attacked. The fighting was heavy and violent, in the mêlée confusion reigned.

After three hours Walt’s Company received orders to “Stand to” and prepare to

reinforce the firing line, the orders continued to come thick and fast, within

a few minutes Walt’s senior company officer, Captain Bramwell received more

following instructions:

By 11pm B, C and D companies were settled into the GHQ line. In the

still of the night the men waited then, at 3.50am, the guns opened up an

intense bombardment of the German lines extending from Railway Wood to

Sanctuary Wood. At precisely 4.19am a mine beneath the German positions was

detonated. A minute later the British, consisting of the Shropshire Light

Infantry, Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, and the 9th Rifle Brigade,

attacked. The fighting was heavy and violent, in the mêlée confusion reigned.

After three hours Walt’s Company received orders to “Stand to” and prepare to

reinforce the firing line, the orders continued to come thick and fast, within

a few minutes Walt’s senior company officer, Captain Bramwell received more

following instructions: “Move 3 companies up at once Railway Wood aaa Situation is that troops after capturing German lines have been forced back and are attacking our original trenches and your Battalion will hold the original lines and original line of ‘H’sector.”

Under cover of darkness Walt and the rest of the men worked hard to repair the trenches and recover their dead. In total 11 men had been killed including Captain Skrine, the A company commander; 38 had been wounded and 2 were missing.

The following day was sunny and much quieter. The men continued repairing trenches and generally reorganising always careful to avoid sniper fire. Despite their caution another six men died this day.

The 27th was uneventful apart from one notable incident which resulted in a rare show of mutual respect on both sides. One poor German soldier had been badly injured and lay moaning in No Man’s land. The Germans had tried several times to recover him back to their lines but were unsuccessful. At 5.30pm they allowed two men from the Somerset’s to reach the wounded man and carry him back to the Battalion trenches. The war diary records

“the operation being concluded with mutual cheers on both sides.”

The following day amidst heavy rain, the Battalion returned to camp.

However before leaving they received a visit from senior officers who expressed

the Corp Commander, General Pultney’s, satisfaction at their work. Following

this verbal pat on the back was a letter to Colonel Rawlings, Commanding Officer

of 43 Brigade to which the Somerset’s were attached.

“Dear Colonel Rawling, I have to thank you and your fine regiment for the great assistance you gave me on the 25th. It was not an easy thing to reinforce, in broad daylight, like you did, and the movement was exceedingly well and quickly carried out. You arrived at a critical time and your dispositions were exactly what was required. The company of your Regiment which formed the garrison of the trenches rendered valuable assistance and I much regret to hear of the losses they sustained.”

On the last day of September, Walt and the remaining members of the

Battalion moved to a camp near Brielen House, 5 miles away, North West of

Ypres.

October was comparatively uneventful although the inclement weather

made life difficult and unpleasant. On the 4th the Battalion occupied some

trenches at St Eloi but soon moved to a rest camp near Poperinghe. Before the

move there were still casualties, one soldier shot and killed as he looked over

the top of the trench, and the following day lieutenant Black was wounded by a

pistol accidentally fired in his face.

On 27th a selected group of Battalion soldiers paraded for inspection

by King George V. The weather that day was, “wretched. Rain all day. Camp very

muddy.”

The final October entry in the Battalion war diary records:

“Training very much hindered by the inclement weather. As far as the regimental officers can judge the work now being done to get the troops under cover might have been begun several months back. Troops suffering great discomfort from the mud and from having to work for hours in the rain putting up mud huts that do not appear to be altogether a success. Large numbers of staff officers appear promising much but very little results from these visits.

Spirits of the men splendid. With incessant rain, plenty of fatigues, no change of clothes, no chance yet of getting warm, they can still stand for hours playing and watching football matches.”

The first three weeks of November 1915 were characterised by the weather, pouring rain reduced everything to wet, sticky and thick mud. After the rain came days of intense cold, hard early morning frost, freezing temperatures and occasional dense fog. The conditions were harsh, uncomfortable and difficult to work in.

On 23rd the Battalion marched from the Brielen area to the front line trenches just north east of St Jean relieving the Durham Light Infantry. Two days in and two days out of the front line was the rule at this time. In reality there was little to choose between the filthy state of the trenches and the miserable conditions found in the billets. The bad weather continued into December but on the 5th Walt and the other men in D Company were instructed to return to Poperinghe where, after many weeks of hardship, they finally managed to have a bath. They were billeted in the rest camp they had vacated six weeks or so before, the men weren’t impressed; it didn’t appear to have changed since their last occupancy, so, in the coming weeks, they set about repairing and generally improving their living conditions. They stayed in the camp until the end of the year without much incident.

On the 19th they received reports that the Germans had launched a gas attack on a position they had only recently vacated. Later the same day they conducted a roll call of each company and recorded the names of all the men.

Walt is listed as Private 10538 Thomas W.R. number 4 company, 6th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry.

The total strength of the company was recorded as 6 Officers and 241 other ranks.

Christmas Day 1915 was spent in the rest camp, Walt, like the others, enjoyed receiving the gifts and luxuries sent to them from the people of Somerset and he enjoyed Christmas in spite of the mud and poor conditions. During the festive period, a rumour was circulating they would soon be transferred to Egypt. All warm clothing had to be handed in and the Battalion was ready to move out at a moment’s notice. Sadly for the men, early on Boxing Day morning, new orders were received, the move was cancelled and they were to return to the Ypres salient in trenches next to the French.

This was a massive blow to morale their thoughts were recorded in the diary:

On 23rd the Battalion marched from the Brielen area to the front line trenches just north east of St Jean relieving the Durham Light Infantry. Two days in and two days out of the front line was the rule at this time. In reality there was little to choose between the filthy state of the trenches and the miserable conditions found in the billets. The bad weather continued into December but on the 5th Walt and the other men in D Company were instructed to return to Poperinghe where, after many weeks of hardship, they finally managed to have a bath. They were billeted in the rest camp they had vacated six weeks or so before, the men weren’t impressed; it didn’t appear to have changed since their last occupancy, so, in the coming weeks, they set about repairing and generally improving their living conditions. They stayed in the camp until the end of the year without much incident.

On the 19th they received reports that the Germans had launched a gas attack on a position they had only recently vacated. Later the same day they conducted a roll call of each company and recorded the names of all the men.

Walt is listed as Private 10538 Thomas W.R. number 4 company, 6th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry.

The total strength of the company was recorded as 6 Officers and 241 other ranks.

Christmas Day 1915 was spent in the rest camp, Walt, like the others, enjoyed receiving the gifts and luxuries sent to them from the people of Somerset and he enjoyed Christmas in spite of the mud and poor conditions. During the festive period, a rumour was circulating they would soon be transferred to Egypt. All warm clothing had to be handed in and the Battalion was ready to move out at a moment’s notice. Sadly for the men, early on Boxing Day morning, new orders were received, the move was cancelled and they were to return to the Ypres salient in trenches next to the French.

This was a massive blow to morale their thoughts were recorded in the diary:

“Great disappointment by all officers and men as after six months of the salient, everyone is extremely wary of the spot, and considering our casualties in the Division, something over 13000 they think that if no more was going to take place our hopes should not have been so buoyed up.”

The poor weather and general living conditions continued into the New Year. On the 4th the Battalion marched out of their camp and boarded a train at Poperinghe having received orders to relieve the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry on the front line that night. On reaching the frontline they found the trenches to be in a dreadful state, “falling to pieces and full of water.”

“The front line is in an almost impossible condition and no troops can remain there more than 48 hours without sickness.”

The return to a wet front line, constant shelling and poor conditions was beginning to try the patience of some of the officers,

“All dugouts constructed by us last time in Canal Bank have been taken over by 6th Division, so our Battalion as usual have to commence building all over again for probably somebody else’s benefit.”

“All dugouts constructed by us last time in Canal Bank have been taken over by 6th Division, so our Battalion as usual have to commence building all over again for probably somebody else’s benefit.”

Gum boots had become another source of irritation, they were in short supply so were constantly being shared amongst the various Regiments. At the beginning of January the Battalion had been handed thigh gum boots in a “very wet condition.” So it was with some relief that by the end of the month each Battalion was issued with their own gum boots and allowed to keep them.

There were some lighter moments. On the 6th several high explosive German artillery shells landed in the nearby canal resulting in a huge explosion and subsequent competition between the men to see who could collect the most small fish killed in the explosion. Hot food boxes were also received and were a big success with the men. On 18th February the Battalion was given orders to move to Ledringhem about 14 miles west of Poperinghe. It was not a straightforward move. Only three lorries arrived to transport the surplus stores the Battalion needed. Although the officer in charge of the transport said he would organise a second journey, he later refused which resulted in Walt and his company having to leave all blankets and stores behind for the night.

They arrived in Ledringhem by 5.30pm and were pleasantly surprised by the quality of their billets which were comfortable, roomy with plenty of straw to sleep on. Two days later they boarded a train at midnight arriving 9 hours later in Longueau near Amiens. It had been a long and uncomfortable journey via Boulogne and Abbeville, packed into cattle trucks. Having disembarked from the train they encountered more logistical problems; there were too few lorries available to help them. Consequently they had to route march the 14 miles to Vigancourt. It was just after three pm, the snow was beginning to fall and being blown into their faces. The men had no greatcoats because they had been loaded onto the few available lorries. To keep up morale the Battalion band containing cornet player Walt, led the march which arrived “smartly “at their billets. Unfortunately they arrived in a small village and the advance party had experienced problems finding sufficient room for nearly 6000 men. Consequently many of the Battalion had to make do and try to be as comfortable as possible with the straw provided, lying on hard, cold ground. To make matters worse the snow was falling more heavily to a depth of a couple of inches.

On 24th February there was still a shortage of lorries so permission was given to hire country carts. The carts loaded with supplies went on ahead and the men began the 14 mile march north to Beauval. At Beauval yet more orders to continue marching north eventually arriving at Humbercourt, south west of Arras with the Somme river nearby. On the way they passed some familiar faces in the 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. Clearly this had been a challenging few days and not surprisingly the men were extremely tired. The diary records:

There were some lighter moments. On the 6th several high explosive German artillery shells landed in the nearby canal resulting in a huge explosion and subsequent competition between the men to see who could collect the most small fish killed in the explosion. Hot food boxes were also received and were a big success with the men. On 18th February the Battalion was given orders to move to Ledringhem about 14 miles west of Poperinghe. It was not a straightforward move. Only three lorries arrived to transport the surplus stores the Battalion needed. Although the officer in charge of the transport said he would organise a second journey, he later refused which resulted in Walt and his company having to leave all blankets and stores behind for the night.

They arrived in Ledringhem by 5.30pm and were pleasantly surprised by the quality of their billets which were comfortable, roomy with plenty of straw to sleep on. Two days later they boarded a train at midnight arriving 9 hours later in Longueau near Amiens. It had been a long and uncomfortable journey via Boulogne and Abbeville, packed into cattle trucks. Having disembarked from the train they encountered more logistical problems; there were too few lorries available to help them. Consequently they had to route march the 14 miles to Vigancourt. It was just after three pm, the snow was beginning to fall and being blown into their faces. The men had no greatcoats because they had been loaded onto the few available lorries. To keep up morale the Battalion band containing cornet player Walt, led the march which arrived “smartly “at their billets. Unfortunately they arrived in a small village and the advance party had experienced problems finding sufficient room for nearly 6000 men. Consequently many of the Battalion had to make do and try to be as comfortable as possible with the straw provided, lying on hard, cold ground. To make matters worse the snow was falling more heavily to a depth of a couple of inches.

On 24th February there was still a shortage of lorries so permission was given to hire country carts. The carts loaded with supplies went on ahead and the men began the 14 mile march north to Beauval. At Beauval yet more orders to continue marching north eventually arriving at Humbercourt, south west of Arras with the Somme river nearby. On the way they passed some familiar faces in the 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. Clearly this had been a challenging few days and not surprisingly the men were extremely tired. The diary records:

“Transport began to come in at 9.30pm. When all first line transport had arrived. No blankets had arrived in the lorries so the men had to spend the night in their wet greatcoats. Billets very bad easily the worst we have so far occupied. Weather frightful all day blinding snow poured into our faces from start to finish. Wind very cold against us all the way. Temperature below freezing point.”

|

| Walter second from left. |

“A Vickers machine gun coy has been formed & 4 Lewis guns have been given us instead, no opportunity has been given to instruct the men owing to lack of time. Eight men went through a four days course & those men comprising 2 a team will have to instruct the remaining men in the line.”

Later in 1916, in a letter home, Walt describes himself as a member of a Lewis gun team, presumably his future role was born this day. Maybe the picture, with Walter standing second from left, records the eight men who completed the four days training.The war diary also painted a vivid picture of what they found in Achicourt. “Trenches in good condition, 8 foot deep, tidy and well constructed;

“The place is extremely quiet. Achicourt about ½ mile from the front line has still about a population of 150 civilians, hardly a house has been damaged and the shell fire is absolutely infinitesimal as compared with the salient, the French casualties being about 8 in the last five months.”

“the line is so quiet that cookers are brought up to Agny, put in houses there and the food will be brought up in the dixies, it will have of course to be heated on arrival.”

Dixies were a large iron pot, often a 12-gallon camp kettle used by the

British Army. In this quite area of the war, March passed without much incident with

few casualties, although on the 2nd March the Germans artillery fired “whizz

bangs” onto Walt’s company and one man was killed. Early in the month heavy

snow made day to day life challenging and difficult, the night brought freezing

temperatures.

In the early hours of 10th March the diary records the fate of one

young German soldier who stumbled upon the British line, when challenged by the

sentries he ran but was shot. The diary records:

The weather warmed and the men enjoyed basking in some sun which made a change from the terrible snow of previous weeks.

There was a Battalion inspection to decide the best turned out platoon, and the men were treated to a demonstration of a new German weapon, the flamethrower.

Zepplins were seen over Arras, British artillery caused German transport horses to stampede, and the unfortunate Captain Walrond was shot in the head and killed by a German sniper as he put his head above the parapet.

April, and the Battalion were billeted in the small village of Agny before moving a few days later to another small village, Berneville. On the 6th Walt and his company completed a route march then spent the afternoon playing football. During this time leave, which had been on hold for the previous months, were increased in an effort to give each member of the Battalion an opportunity to return home. Probably while in Berneville Walt wrote a letter home, probably addressed to one of his older sisters, Lillian or Marion. It was dated the 11th April 1916 which, if correct, meant he wrote it from nearby trenches because by the 10th the Battalion had left Berneville and returned to the trenches near Agny. In the letter he makes reference to Ypres.

There was a Battalion inspection to decide the best turned out platoon, and the men were treated to a demonstration of a new German weapon, the flamethrower.

Zepplins were seen over Arras, British artillery caused German transport horses to stampede, and the unfortunate Captain Walrond was shot in the head and killed by a German sniper as he put his head above the parapet.

April, and the Battalion were billeted in the small village of Agny before moving a few days later to another small village, Berneville. On the 6th Walt and his company completed a route march then spent the afternoon playing football. During this time leave, which had been on hold for the previous months, were increased in an effort to give each member of the Battalion an opportunity to return home. Probably while in Berneville Walt wrote a letter home, probably addressed to one of his older sisters, Lillian or Marion. It was dated the 11th April 1916 which, if correct, meant he wrote it from nearby trenches because by the 10th the Battalion had left Berneville and returned to the trenches near Agny. In the letter he makes reference to Ypres.

April 11th 1916

Dear Sister,

I have received your letter & I am glad to hear that you are all well & in the best of health. I am sorry you made him cry, will you help him for me, because I am keeping them. I haves a look at them now and again & haves a good laugh to myself. I can’t help it when I sees his spelling. I haven’t had that parcel from Mrs Little, this is the first I’ve heard of it. We have started leave again & I hope to be able to come soon. I am glad that you have seen the pictures, I have walked through there with my heart in my mouth & I tell you I don’t want to see the place again. It is alright where we are now, tell mother I am very glad that she is getting better, & I shall be home before long. Give my love to all and tell them that I am in the best of health from your ever

loving Brother.

Walt

xxxxxx

xxxxxx

More than one of Walter’s sisters wrote letters to him. On a wet April day whilst resting in a village near to Agny he replied to a letter from his 10 year old sister Dora.

Dear Dora

Just a few lines to let you know that I have received your letter & I am glad that you are all in the best of health. I have got your photo, ask mother & father if they can have their photos taken & send me one. I am in the best of health & getting on a treat. I am glad that Alice got her medal, see if you can get one. Broncho told me about Mr Hopton & I am glad they made a collection & bought him a present. Dear Dora told mother & father that leave is stopped again & I don't expect to be home for a long time yet & tell them not to worry because I am in the best of health. I must close now hoping you will write again soon.

From your ever loving Brother

Walt

xxxxxx

From his billet in Dainville and following a billet inspection by the Brigader General commanding 43 Brigade, Walt wrote the following letter home:

19th April 1916

Dear Dora

Just a few lines to let you know that I have received your letter & I am glad that you are all in the best of health. I have got your photo, ask mother & father if they can have their photos taken & send me one. I am in the best of health & getting on a treat. I am glad that Alice got her medal, see if you can get one. Broncho told me about Mr Hopton & I am glad they made a collection & bought him a present. Dear Dora told mother & father that leave is stopped again & I don't expect to be home for a long time yet & tell them not to worry because I am in the best of health. I must close now hoping you will write again soon.

From your ever loving Brother

Walt

xxxxxx

May began with time away from the front at Berneville before moving to a rest camp at Dainville, then days on the front line trenches near Agny before returning to Danville. The warmer weather had given way to wind and rain, the artillery exchanges and machine gun fire was comparatively light although Walt’s Company suffered a mortar attack whilst in the trenches. These mortars were known as “Crashing Christophers.” Thankfully there were no casualties.

Although April and May had been relatively uneventful there was a gradual increase in activity on both sides, shelling was becoming more frequent and snipers were claiming more victims. Private Fred Yendall also in D Company was a friend of Walt who had returned home recently on leave.From his billet in Dainville and following a billet inspection by the Brigader General commanding 43 Brigade, Walt wrote the following letter home:

I received your letter yesterday. I am glad that you are all well. I am in the best of health, it is hot out here & I am glad that Broncho looks alright in his scouts clothes. Will you have his photo taken & send me one. Fred Yendall left here yesterday on his way home & I hopes to be able to come in a couple of weeks time so don’t worry. Dear mother I knows where Bristols own are, they are only a couple of miles from we, so I will keep my eyes open because I might drop across him any time & I should like to see him. I have received the P.O. alright & I will keep my open for the parcel. Dear mother give my best love to all, I will write again in a couple of days time, hoping you are all in the best of health.

From your ever loving son.

Walt

June continued much like the previous months, the Somerset’s sharing front line trench duty with the Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry. As a consequence of increased fighting in the Vimmy Ridge area north east of their positions, several heavy British artillery units left the Agny region. Leave was reduced to one day allotted every 4 days for the whole Battalion, and the men were made aware of shipping losses at the battle of Jutland.

On the 21st Walt and the rest of the Battalion moved to new positions in the Blangy district north east of Arras. The trenches were not in as good a condition as those they had vacated in Agny, furthermore the frontline ran directly through the village of Blangy where the German lines were just 10 yards from the British. Snipers were everywhere and causing may casualties. The weather was hot with the occasional thunderstorm at night. The night before the beginning of the Somme offensive, Walt and the rest of the Battalion were in Blangy and could hear the distant thud of artillery fire south of their position. The allied offensive had begun.The frontline positions held by Walt and the other men were unusually quiet in early July. The Somme offensive had caused the German army to pull men away from the Blangy sector. The opposing trenches in this part of the line had been pushed forward to within yards of each other in places. A “sap” was a narrow trench cut at an angle towards the enemy line. At one point one sap occupied by the Somerset men was within 5 yards of an opposing German sap while the trenches were only 15 yards apart. A bomb or grenade could easily be thrown into the opposition line. The war diary records:

“When a bomb is thrown over the Germans get very annoyed and reply with about 60 into our sap.”

On the 21st July orders were received instructing the Battalion to move to the small village of Agnez-des- Duisans. The following night they were relieved by men from the Kings Shropshire Light Infantry and in the early hours began their march west to new billets arriving at 3am on the 23rd. Life in their new billets was much quieter and offered a chance to rest. That rest for Walt and a 100 other men from D company, was interrupted when they were deployed into Arras to help construct a trench tramway. Trench railways linked the front with standard gauge railway facilities beyond the range of enemy artillery. Walt and the others returned a day later but their down time in Agnez-des-Duisans was limited. The Battalion had received new orders to move out and redeploy to Warluzel an 11 mile march south west of their current position. The men set out at 10am on the 28th. It was a hot summer’s day and each man carried full packs. It was a difficult and demanding march with 27 men struggling to complete it.

On arrival at yet another set of billets the men found the facilities to be relatively comfortable. However it was only a brief respite as another, longer and just as challenging march lay ahead, 13 miles west to yet another tiny French village, Villers L’hopital. Again the heat was overpowering and although they stopped for a ten minute rest every ten to the hour, still 47 men struggled and fell by the wayside and needed to recover before continuing. 6 ½ hours later they arrived at their new billets where later that evening 150 men reported sick to the medical officer. The war diary entry records the problem.

On arrival at yet another set of billets the men found the facilities to be relatively comfortable. However it was only a brief respite as another, longer and just as challenging march lay ahead, 13 miles west to yet another tiny French village, Villers L’hopital. Again the heat was overpowering and although they stopped for a ten minute rest every ten to the hour, still 47 men struggled and fell by the wayside and needed to recover before continuing. 6 ½ hours later they arrived at their new billets where later that evening 150 men reported sick to the medical officer. The war diary entry records the problem.

“There was rather a scarcity of water on arrival owing to most of the wells in the village either being deficient of rope or buckets this was rectified as soon as possible. The troops were very tired & could not possibly have gone much further.”

After a day of “rest,” Walt and the rest of the men were on the march again, this time 8 miles south to the village of Prouville where they stayed for the next 6 days. During a quiet moment Walt wrote another letter home:

August 1st 1916

Dear Mother & Father

I have just received your letter dated 24th July & I am glad to say that I am in the best of health & getting on a treat & I am very glad to hear that you are all well. Dear mother don’t get worrying so much, because I am alright & in the best of health & that is what you want, is a good holiday & when you write again, let me know how you have enjoyed yourself, but don’t get staying at home all the time because of me, because I am alright. I am very glad that Lil & Ivor has enjoyed themselves & I hope to hear that you have done so the next time you write. I have received the parcel & Lil’s card & I wrote a letter to say so about four days ago, perhaps you will receive it soon. Dear mother I am very sorry to hear that they made a mistake about Alice, but never mind, a couple of months won’t make any difference. I shant know them when I comes home, Broncho looks big on his photo & Sammy looks in the best of health, do you have much trouble with them now. Dear mother we are out for a rest & I am writing this letter along way behind the line so don’t worry, give my love to all & don’t forget, you and father have a good holiday. It will do you good.

With best love from your ever loving son,

Walt

xxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxx

PS Have just received your parcel dated 28th. Walt.

Ominously the diary records parades and route marches to get the men “fit.” One entry reveals,

“orders have been received that the men must be made as fit as possible in 4 days, as we shall probably go in the show at Albert shortly.”

“orders have been received that the men must be made as fit as possible in 4 days, as we shall probably go in the show at Albert shortly.”

|

| Méricourt-l'Abbé 2016. |

At 3.15pm on the 6th August the men marched to Candas where they boarded a train for Méricourt-l'Abbé. After many delays and stoppages they finally arrived at their destination then onward, marching to a campsite on top of a hill overlooking the town of Albert. Walt set his bivouac on the side of the hill not knowing how long they would be staying. He didn’t have long to wait. At 5am on the 9th, the Somerset’s commanding officer, Colonel Ritchie, and the four company commanders paid an early morning visit to Delville Wood situated about seven miles east of the campsite.

|

| Fields overlooking Albert. 2016. |

Later the Germans made a weak attempt at attacking one of the British saps but were repelled easily by the Battalion. During this engagement a number of Somerset men were wounded and killed including several officers, also a young German deserter came over to the British side having first destroyed all his papers and was taken prisoner. It was a considerable relief for all when the Battalion were finally replaced by The Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry and returned to support trenches in Montauban Alley west of the front line. Although held in support, the Somerset men had not finished with Delville Wood. 250 soldiers spent two consecutive nights working and preparing trenches in the wood, created so British troops could assemble before a major attack. At 3am on the 18th all four companies moved from Montauban, to assembly positions at the south east corner of Delville Wood. Walt and the rest of D Company prepared themselves and lined up in a trench to the rear of A and C Companies. Everyone was ready and in position by 6am. The attack was to be proceeded by a British artillery bombardment, but so difficult was the terrain and conditions that observation for the British Gunners was limited and consequently some shells fell onto their own men. 15 Somerset soldiers were injured.

“our heavy guns were firing short nearly all morning repeatedly hitting our trenches & causing casualties, our men in the end became more afraid of our guns than the Germans.”

At Zero hour, 2.45pm, the attacking troops went over the parapet into No Man’s Land and found themselves under the barrage just 25 yards or so from the German trenches. Here they had to halt, for a full five minutes, until the barrage lifted. As soon as the artillery screen moved on, the men found themselves in the German trenches, bayoneting and shooting the German soldiers who refused to surrender.

“Many German prisoners were captured, they were in a very demoralised condition & surrendered without even putting up a fight, the Battalion captured about 200 although we were not credited with this amount owing to most sending them back under our escort. Four machine guns were captured two of which were used by us to help consolidate the line.”

|

| Delville Wood, the general area of Bitter and Beer trenches |

|

| Walter and the Battalion advanced on Railway Wood across these fields. |

“the men on arrival in rest billets were absolutely beat, the authorities had wisely left them until the last possible moment & then taken them out.”

This particular battle at Delville Wood was over. The Somerset’s had lost 53 men killed including Lieutenant Denton, Walt’s second in Command, and over 200 wounded, or missing. From the peace of Fricourt, Walt penned his most dramatic, vivid and disturbing personal account of the fighting in his subsequent letter home to his parents.

Aug 21st 1916

Dear Mother, and Father,

I have received three letters, two from you and one from Lil and I am very glad to say that I am alright & in the best of health. Tell Bronco to hurry up and write because I am waiting to hear from him. I am very glad that Charlie is out of it, he is lucky & and I am glad that Uncle Ernest is well. Dear Mother I don’t think there will be any leave yet, but I will try hard at the first opportunity. Dear Mother you will be glad to know that we have been over the top & have taken two lines of trenches, it was the first time this Battalion has been at close quarters with the Germans & it has made up for all the hardships we have suffered. Dear mother it was the finest bit of sport since we have been out here, it was a fine night, we were all lined up on the parapet & started to walk across (not running mind) to the Germans about 400 yards to their first line & there wasnt a German there, in fact, a lot of us didn’t know it was the second line we were in, because their first line was nothing but a lot of shell holes & when the Germans saw us up went their hands & kamarad, kamarad, mercy, mercy they started shouting & I saw with my own eyes about 20 of them on their hands & knees & crying their eyes out. Dear Mother I am on the Lewis gun there is six in a team I was a reserve man & one of the teams got blowed up by a shell & I had to go I was carrying a pannier, that is four magazines of ammunition for the gun & when I reached the second line I hopped in the trench & I saw two Germans taking the cover off a machine gun & I dropped the ammunition I was carrying & put the two Germans out of mess with the Bayonet & shot 3 as they were running back to there reserve but I never had the heart to shoot any with their hands up, but some did get put out like it in the excitement, it couldn’t be helped, there was we itching for a fight when we got there they gave themselves up & all as I can say about Germans after that, is that they are nothing but a lot of cowards. Dear Mother I am sending you a couple of German post-cards & I have got a belt for Father I will try and send it home as soon as I can so look out for it, give Charlie one of these cards for a souvenir from me & tell him I wish him the best of luck. This belt & post-cards is off the German that I bayoneted & I have got a couple of buttons off the same bloke for Broncho. We took the trenches on the 18thof this month. Give my love to all from your ever loving son

Walt

xxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxx

Later the same day the men received a visit from the Brigadier who congratulated them on their“fine performance at Delville Wood.”

After a few days rest they were back in the firing line, mostly in support of other regiments around the Delville Wood area. Although mainly in a support role the casualties continued to mount. By August end the rain was falling, trenches were sodden and utterly water logged. Rum kept the men’s spirits up, but a large British attack was cancelled due to the poor weather. On the 30th, the Somerset’s were occupying Pommiers redoubt, (a temporary fortification built to defend a position)before being relieved by the Queens regiment. From temporary bivouacs in Fricourt, they received orders to board a train at Mericourt. Arriving at Amiens, the soldier’s packs were loaded on to lorries and the weary soldiers prepared for yet another march, nine miles to the village of Selincourt. The diary records,

“owing to men’s feet being so bad the pace was not good but the men came on splendidly very few falling out.” “No hot food on was ready on arrival, the men were very tired & comfortable barns were provided so that not much time was lost settling in.”

In Selincourt everyone enjoyed complete rest. Walt had time to write home but, at such a sensitive time, military censorship restricted soldier’s letters to a standard post card. The post card was pre-printed with a number of options. Soldiers were only permitted to delete non relevant options and sign and date the card.

Walt’s card reads:

“I am quite well.”

“I have received your parcel.”

“Letter follows at first opportunity.”

“I have received no letter from you lately.”

W R Thomas

10.9.16

The Somerset Light Infantry were part of 43 Brigade who in turn formed part of the 14th Division of the British Army. Although not directly involved at this time, for Walter and the other soldiers the 15th would prove to be a memorable and historic day. The British army launched the Battle for Flers-Courcelette which was notable for the introduction of tanks. The attack was launched across a 12 km front and involved twelve divisions including all the tanks the British army possessed. It was the first time tanks had been used in warfare and for many soldiers their first sight of these cumbersome, but morale boosting machines. Unbeknown to Walt and the other Battalion members, their sister Battalion, the 7th Somerset Light Infantry were close by, east of the 6th's position and also preparing for an assault the next day.

Lieutenant Henry Foley, a 7th Battalion Officer vividly described the scene on that momentous September day, the last full day of Walters’s life:

"It was a warm afternoon with bright sunshine. The Germans were shelling Delville Wood and Ginchy. A few Indian cavalrymen were seen riding past on their return from the front and now we were able to recognise the engines of war which had caused such a noise during the night. We had a close view of two of the tanks that had come into the action for the first time that morning. They were returning from the battlefield for refit. These armoured mobile fortresses caused us no end of surprise, they looked so ungainly and heavy, but it was wonderful to see how they negotiated trenches and obstacles."

By 5pm the British attacks had pushed the Germans back on average one mile across a six-mile front. Another 7th Battalion Officer, Captain Jones recalled:

"As the evening fell the air became cold and there was a fairly bright moonlight. The night was still and there was not much shelling. Rumours began to float around that our Brigade would have to attack the next morning. At 9.45pm orders were received that the Brigade was to attack the next morning at 9.25am."

Walt and the rest of the Battalion were ordered to attack and seize two German defensive trench networks called “Gird trench” and “Gird support.” These trenches lay north east of the village of Flers, which had been captured the previous day. They were to relieve the 9th Battalion of the Kings Royal Rifles on the front line, who occupied recently captured trenches known as “A-A” and “B-B.”

After the relief, the Battalion were spread across a relatively small area. B Company held the right side of “A-A” and C Company the left. A Company was in “B-B” trench and Walt and the rest of D Company were positioned in support of the other 3 companies in a position known as “Gun Alley.” Lance Corporal Arnold Ridley was also present and later recalled,

After the relief, the Battalion were spread across a relatively small area. B Company held the right side of “A-A” and C Company the left. A Company was in “B-B” trench and Walt and the rest of D Company were positioned in support of the other 3 companies in a position known as “Gun Alley.” Lance Corporal Arnold Ridley was also present and later recalled,

"The trenches were full of water and I can remember getting out of the trench and lying on the parapet with the bullets flying around because sleep was such a necessity and death only meant sleep."

No rations had arrived so the men had to prepare to fight with little food and even less fresh water. Eventually provisions for two companies were provided, but the other two had to survive on their iron rations. The so-called 'Iron Ration' comprised a ration of preserved meat, cheese, biscuit, tea, sugar and salt and was carried by all British soldiers in the field for use in the event of being cut off from regular food supplies.

The attack was to be made by the companies in the front line, in two waves. The first objective being Gird Trench. Once captured they would continue moving forward, with artillery support and capture Gird Support. Due to poor reconnaissance, unbeknown to the commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Ritchie, there was another trench which he later called “X-X” just beyond “A-A” but out of view due to the deceptive undulating topography of the land.

At zero hour, 9.25am the attack began. The three attacking companies A, B, and C, followed the barrage and soon reached what they thought was their first objective, the German, “Gird Trench.” However what they actually had reached was the previously unknown “X-X” trench. Six Germans were captured and about a hundred were seen running away. When coming over the ridge between “A-A” and “X-X” trench the Somerset men had come under heavy German shelling and machine gun fire from German positions to the north and east.

One particular machine gun position caused much of the carnage; it was situated on higher ground to the right of the advance near the village of Les Beoufs. The men were also coming under mortar bomb fire from “Gird Trench.”After 25 minutes of intense fire B Company sent a message saying they couldn’t advance due to the German resistance and heavy fire. Walt and the other men of D Company were sent to help B Company now pinned down in “X-X” trench. It was during this engagement that Walt was killed, most likely shot by the heavy machine gun fire coming from Les Beoufs. The attack failed to reach the German lines let alone liberate Gueudecourt. The remainder of the Battalion, supported by one company from the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, held on in “X-X” trench through the night until day break when they were relieved.

Four regiments took part in the attack, The Somerset Light Infantry, Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, Durham Light Infantry and the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry.

The Somerset casualties were truly horrific. Every officer who went over the parapet (and there were 17), had become a casualty. Three had been killed, twelve wounded and two were missing. In other ranks the Battalion had lost 41 killed, 203 wounded and 143, including Walt, were listed as missing in action. Overall 1,391 men had been killed, wounded, or were missing believed killed.

The ridge between “A-A” and “X-X” trenches had been a killing ground. Sadly Walt’s body was never found. The 142 other men reported missing at the same time as Walt, evidenced the complete destruction and slaughter of that attack.

The attack was to be made by the companies in the front line, in two waves. The first objective being Gird Trench. Once captured they would continue moving forward, with artillery support and capture Gird Support. Due to poor reconnaissance, unbeknown to the commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Ritchie, there was another trench which he later called “X-X” just beyond “A-A” but out of view due to the deceptive undulating topography of the land.

At zero hour, 9.25am the attack began. The three attacking companies A, B, and C, followed the barrage and soon reached what they thought was their first objective, the German, “Gird Trench.” However what they actually had reached was the previously unknown “X-X” trench. Six Germans were captured and about a hundred were seen running away. When coming over the ridge between “A-A” and “X-X” trench the Somerset men had come under heavy German shelling and machine gun fire from German positions to the north and east.

|

| The undulating topography which hid X-X trench. Me holding a picture of Walt. |

Four regiments took part in the attack, The Somerset Light Infantry, Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, Durham Light Infantry and the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry.

The Somerset casualties were truly horrific. Every officer who went over the parapet (and there were 17), had become a casualty. Three had been killed, twelve wounded and two were missing. In other ranks the Battalion had lost 41 killed, 203 wounded and 143, including Walt, were listed as missing in action. Overall 1,391 men had been killed, wounded, or were missing believed killed.

The ridge between “A-A” and “X-X” trenches had been a killing ground. Sadly Walt’s body was never found. The 142 other men reported missing at the same time as Walt, evidenced the complete destruction and slaughter of that attack.

|

| Looking towards Gueudecourt and German defensive positions. The undulating ground is deceptively hidden. The 6th Somerset Light Infantry killing field. 2016. |

19.9.18

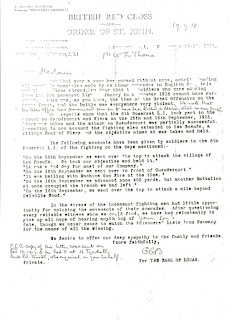

Dear Madam

Now that over a year has passed without news, notwithstanding all possible enquiries made by us among comrades in English hospitals, and abroad, we fear that the soldiers who were missing from the 6thSomerset Light Infantry in September 1916 cannot have survived. This was, as you know, the time of the Great Offensive on the Somme front, and the battle was everywhere very violent. We note that the War Office has pronounced your son to have been killed a decision which we never questioned.

Now that over a year has passed without news, notwithstanding all possible enquiries made by us among comrades in English hospitals, and abroad, we fear that the soldiers who were missing from the 6thSomerset Light Infantry in September 1916 cannot have survived. This was, as you know, the time of the Great Offensive on the Somme front, and the battle was everywhere very violent. We note that the War Office has pronounced your son to have been killed a decision which we never questioned.

Our reports show that the 6th Somerset L.I. took part in the attack on Gueudecourt and Flers on the 15th and 16th September, 1916. Flers was taken and the attack on Gueudecourt was partially successful. According to one account the fighting also extended to Les Boeufs, a village east of Flers and the objective aimed at was taken and held.

The following accounts have been given by soldiers in the 6th Somerset L.I. of the fighting on the days mentioned :-

“On the 16th September we went over the top to attack the village of Les Boeufs. We took our objective and held it.”

“It was a bad day for most of our Company.”

“On the 16th September we went over in front of Gueudecourt.”

“It was hailing with Machine Gun fire at the time.”

“On the 16th September we advanced some 400 yards, but another Battalion at once occupied the trench we had left.”

“On the 16th September, we went over the top to attack a mile beyond Delville Wood.”

In the stress of the incessant fighting men had little opportunity for noticing the movements of their Comrades. After questioning every reliable witness whom we could find, we have had reluctantly to give up all hope of hearing anything of your son’s fate, though we never cease to watch the Prisoners’ lists from Germany for the names of all the missing.

We desire to offer our deepest sympathy to the family and friends.

Yours faithfully

PS A copy of this letter was sent on Dec 12. 1917, to the Red X at 36 Tyndalls Park Rd, Bristol who enjoined on your behalf.

No comments:

Post a Comment